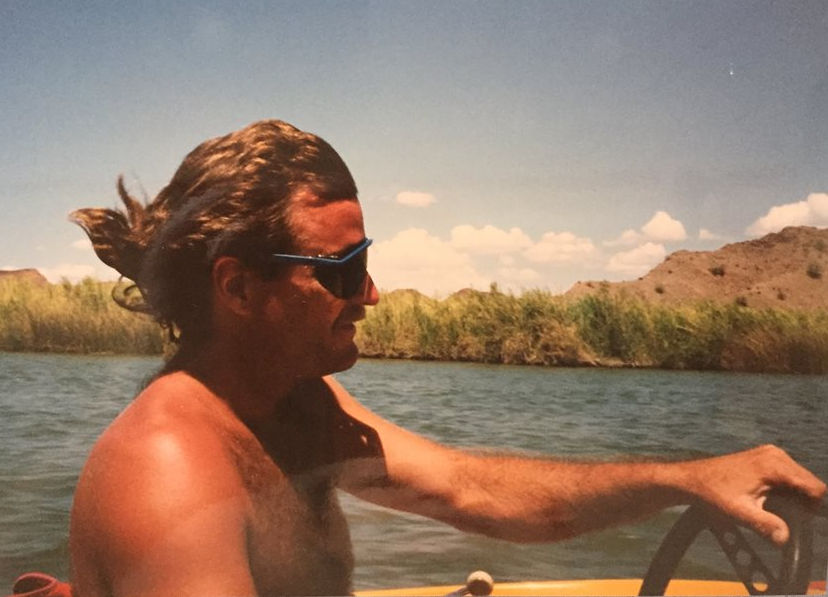

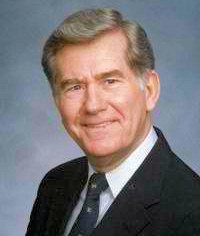

Earl Ryals

With the Old Breed: Earl Edison Ryals

Memoir by Michael Usey

August 24, 2012

Clarence Barton, one of my ministry supervisors in seminary, told me once that in every city there are people who are the quiet servant leaders of that place, and that a good pastor will seek those type of people. They may or may not be prominent or be well known, but they are nevertheless the spiritual backbone of that town. They are the ones who have touched so many people’s lives that it’s hard to meet someone who hasn’t been changed in some way by them. I believe that we have come to remember such a man today in Earl Ryals.

The proper name of a Christian funeral in the Baptist tradition is a witness to the resurrection. We come together with God and family and friends to do several things:

- to remember Earl’s life and loves;

- to give thanks to God for who he was, and how he changed us;

- to grieve his loss among us;

- to celebrate the way Earl loved each of us, taught us, cared for us, because in his love, teaching, and care, we saw God;

- to tell stories about Earl, because none of us know all of them;

- to hold in our hearts the belief that Earl is now with God, in God’s eternity, to love and to serve God forever;

- to comfort one another in our grief at losing such a man;

- to express our relief that he suffers no more, and his work on earth is done; and finally

- to recall the ways in which we saw God through Earl, the manner in which his life was a window to Christ, and how he was a conduit of God’s love to us all.

You’ll read some of the facts about his life in his obituary. You’ve also read Juanita Lojko’s very fine speech honoring Earl on All Saints’ Sunday last year, in which Earl received the Senior Leadership Award from this very church. In a moment you’ll heard from his family as well as a eulogy written by his wife of 66 years, Inez. Hopefully, in these we will get a glimpse of who Earl was with us, and how the divine shined through his words, his actions, and his love. We at College Park are somewhat obsessed with this at our funerals, which is why our services are a blend of homily and eulogy into a memoir, attempting to honor the unique manner in which God loved us through one’s person’s life.

Earl was my friend. So I wasn’t too surprised when, a dozen years ago, he called me up in my office and asked for me to visit him in his home. I did, arriving on the appointed time, curious. Inez and Earl received me in their lovely living room, and plied me with sweet tea and cookies. We chatted about the church, my children, Brenda, their travels, his walking discipline, how one’s attitude could change one’s life and those around you. It was an interesting, enjoyable time. Then, after I’d been in their home for an hour, he asked Inez if he could speak to me alone. Surprised, she consented and left us alone. It was then I discovered the purpose of my visit.

For the next hour and a half, Earl told me some about his military service. As you know, Earl was a Marine, having served in the Pacific theater for three years in World War 2. He told me stories about his time in the service, and his tales were strong stuff. He told me about rotting coconuts on far flung islands that they had to haul away to keep the smell down, and about sand crabs that were ubiquitous on some of the islands. He told me how well the Navy sailors that had transported them treated him, and about some of the Seabees that build the bridges that they crossed. He told me about the mud and the rain, and the rashes on his body that resulted from lying in all that wetness, how the rains would start just like someone had turned on a shower, and stop just as abruptly and suddenly.

I listened while he talked about Japanese snipers who killed men he knew. Earl talked about keeping his gun in working order like it was holy thing, even when the rest of his was a mess. He said there was a point on one of the islands when he and the other Marines realized that none of the Japanese would ever surrender, that they would have to kill them all, or be killed. He wondered aloud why he had not been killed or maimed, when so many that he knew had been. Apparently he had seen lots of dead soldiers’ bodies—some American and many Japanese, and they were ghastly sights that he still remembered vividly. He said to me words that I knew must be so very true: “Michael, you just cannot imagine how much like hell some of these places looked like after a battle.”

He spoke about the camaraderie among his fellow Marines, how close they were, and how he still felt those bonds, even though he had not heard from most of them since he left the Marines. Men in battle were closer than those in business, and he learned lessons there about espirt de corps that he had carried into business. For example, if you took care of a group’s morale, then many other things fell into place.

Earl spoke about the banality of war too: how bored they were when they were aboard ship, or waiting to know where they would go next. He told me how being dry and clean was next to impossible on these far-flung Pacific islands, but they never stopped trying. How sometimes the food tasted so good, like on the recovery bases, and how other times it was the same canned rations repeatedly.

Years later, I read E.B. Sledge’s remarkable memoir of his experience as a Marine in the Pacific during World War 2 entitled, With the Old Breed. The title is a reference to what John W. Thomason called the Marines, the Leathernecks he served with and described in his book Fix Bayonets: “They were the old breed of American regular, regarding home and war as an occupation; and they transmitted their temper and character and viewpoint to the high-hearted volunteer mass which [were] the Marines.” I thought then and do so now give thanks for the bravery of those who fought under the worst possible conditions far, far away from home and kin, for what they believe in.

Earl of course saw acts of extraordinary bravery, guys carrying stretchers under enemy fire, and people being incredibly calm under bombardment. He said he saw fellow soldiers being kind in the midst of extraordinary cruelty, and a few times he saw the opposite. He saw the bodies of American soldiers that had been desecrated by the enemy in the worse ways. And he told me that he saw firsthand the evidence of torture on soldiers of both armies, the memory of which sickened him still. I believe these memories were the reason he was telling me some of his experiences.

Some of the worst he didn’t wish to share with his wife or his daughter. I believe this was incredibly common in men of his generation. My own father was a Navy Lt. Commander, and he rarely spoke of his service in three wars, never when I was young, and only very little when I was an adult. I didn’t realize it then, but I think Earl had an inkling that something was happening to his memory. He was already aphasic, and there were times in this talk that he reached for the right word and couldn’t grasp it. I think he wanted to confess—not of any wrong he’d done—on the contrary I think he acted nobly under horrible circumstances. No, I think he wanted to confess the remarkable and horrible things he’d seen, and for me it was a holy moment.

We asked so much of that generation of soldiers: to live through terrible battles, to see friends slaughtered, to fight and bury comrades, then to return home and live normal lives, as if nothing had happened. To hold all this in, without the release afforded soldiers today, must have been painful, but you have never known it to know Earl.

And finally this story of Earl’s: in his first deployment on the one of the islands, he was in a foxhole at night, two to a hole, and the holes stretching in a line to mark where they had advanced that day. Each man in a foxhole took turns sleeping and keeping watch. And in the dead of night, one of two things typically happened. Either enemy soldiers came to them suddenly out of the woods, or women and children came to them running for their lives. The Japanese would release their so-called comfort women, women they had raped and their children. The problem was in the pitch black you could not tell enemy soldiers from comfort women until they were right up on you. You could hear someone coming before you saw who they were. The soldiers were told to shoot first, and many did. But Earl could not live with the possibility of having shot a woman or child accidentally in the dark of night. He decided he would wait until he saw who was coming before he shot, and if necessary, fight a Japanese soldier hand to hand in his foxhole. I believe this decision—made under the most stressful circumstances imaginable—showed Earl’s character, his Christian commitment, and the trajectory that his life took. Even then he was willing to make his own decision, to risk his life not to kill a non-combatant, even if risked his own safety. There is so much of Earl in the decision long ago, to put himself at risk in order not to shot a woman or a child. Which is why we are all here today, remembering him and giving thanks for the many ways he lived for others—which is the heart of our Christian faith.

OBITUARY

Earl E. Ryals, age 88 of Greensboro, NC died on Saturday August 18, 2012, at WhiteStone Care & Wellness Center. A Funeral Service will be held at 11:00 AM on Friday, August 24, 2012, at College Park Baptist Church, in Greensboro, with burial following at Westminster Gardens .

Born in Coats, NC, he was the son of the late Clarence Edgar Ryals and Mary Byrd Ryals. He served three years with the US Marine Corps in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

His numerous educational and advanced professional credentials included an extensive number of the professional programs offered by the American College, Bryn Mawr, PA, most prominently the Chartered Life Underwriter designation, Agency Management and Agency Officers Schools. His career with Southern Life Insurance Company spanned a period of 43 years. Prior to his retirement in 1988, he served as Executive Vice President and member of the company’s Executive Committee, overseeing the company’s marketing operations in 42 states. His membership in professional organizations through the years included President of Greensboro Better Business Bureau. He served as President of Piedmont Sales Executives and Chairman of the Southeastern Training, Directors Association. As a member of the Life Insurance Marketing and Research Association, he held several positions which included the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the Company Operations Advisory as well as Chairman of the Combination Companies Executive Committee. He was President of Greensboro Chapter of the American Society of Chartered Life Underwriters, and a Board member and treasurer of the NC Insurance Education Foundation. For over 50 years, he was a member of the Masonic Lodge #284 Greenville, NC, 32nd Degree Master Mason and a Shriner. He was Board Chairman and President of the UNC-G Associated Campus Ministries. In 1957, the Ryals family became members of College Park Baptist Church. Earl served as Chairman of the Board of Deacons, and taught Adult Sunday School classes, including college students. He participated in the College Parent Program for students away from home, resulting in lasting friendships with the Ryals family. In 2011, the Church presented him the Servant Leadership Award. Earl’s greatest personal honor was serving on the Board of Trustees, Campbell University, Buies Creek, NC.

Earl Ryals is survived by his wife of 66 years, Inez Stone Ryals and daughter, Brenda Pirko. Grandchildren Robert J. Padgett, IV (Andra), Jason Earl Padgett (Megan), Thomas Joseph Pirko, Kathryn Byrd Fleming. Great grandchildren, David, Noah, Aryn Padgett and Drew Gardner, Mason and Gavin Padgett, Amber and Inez Pirko. Sisters, Edna Blackwelder, Greensboro, NC; Grace Parrish (Craig), Benson, NC; brothers, Harold Ryals (Frances), Raleigh, NC; Donald Ryals (Carol), Angier, NC. Deceased sister, Geraldine Moore (Ed), Angier, NC. Earl was blessed with his much loved nieces and nephews. Special thanks to niece Kay and nephew Richard Blackwelder for their loving support. The family will be at Forbis & Dick North Elm St. Funeral Home, Greensboro, NC, between the hours of 6:30 and 8:30 PM on Thursday.

Memorials may be made to: The Earl and Inez Stone Ryals Scholarship Fund, Campbell University, PO Box 116, Buies Creek, NC 27506 or College Park Baptist Church Capital Campaign, 1601 Walker Ave., Greensboro, NC 27403. Our appreciation goes out to the staff of WhiteStone Care and Wellness Center for their excellent care. Our grateful thanks also goes out to the Hospice Team for their care, encouragement and kindness to Earl and his family.