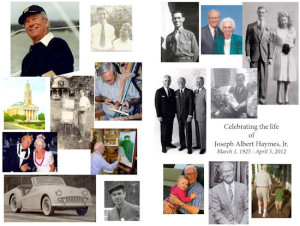

Joseph Albert Haymes, Jr.

Joseph Albert Haymes Jr.: A Faithful Attention to Life’s Sweet Details

(Peggy Haymes’ father)

Memoir by Michael S. Usey

April 9, 2012

How best are we to live this one brief life that we’ve been given? This is the unstated question of every funeral we attend, for in every case some one we know and likely love has given their life for his answer. All of us know that this life is extremely short. I’ve met more than one senior adult who said just yesterday they were teenagers and suddenly they woke up one day to find themselves getting AARP membership offers in the mail.

Like many of you who are Christians, I believe that our lives demand a creation spirituality as a daily focus to our living. By creation spirituality I mean that the twin tasks of living are enjoying the world and trying to change it. We are called by God to enjoy our remarkable lives: Another incredible spring, good food with close friends, and a hot shower after a game of golf on a gorgeous spring day. On other hand, creation spirituality also demands that we see the brokenness of the world and do something to repair it.

It’s a tricky balance, learning how to do both well. Way too many people think that all they are called to do is enjoy life, without having to give anything back. Pleasure for its own sake is ultimately boring. Others try to repair the world but without the intense joy God intended for each of us to have; they seemed to forgotten how to appreciate all the love, joy, and peace God offers us in this place. Both of these options are unbalanced, and ultimately not what I believe God calls us to become, in our best, truest selves. And of course too many attempt neither task, living their lives without joy and without loving neighbor.

As many of you can attest, Joe had a wonderful blend of both enjoying the world God gave to us, and trying to repair its broken places. You know that Joe and Gerry were born in Lynchburg, Va.; she was older than him by eight hours, she on February 28, Joe on March 1. He loved to remind her that he had married an older woman—and every leap year gave him a whole extra day to do it.

They were in the primary department together, and Joe remembers sitting in rows as children, girls in one row, boys in the next. He remembers eighty-plus years ago sitting behind Gerry and looking at her golden curls. He wanted to reach out and run his finger through one of them, but that was a much different time, and he knew there would be payback.

Joe was a sniper in the Army. The higher-ups loved Joe’s recon reports because he was able to draw exactly what he’d seen. There was a rolled jeep down a mountain in Austria that Joe was involved it, maybe even driving, but what exactly happened isn’t clear. Joe paid a guy to teach him German. Why do you want to learn, the man asked; most GIs just want to learn pick up lines. To woo women, so that I can carry on a conversation with them, Joe answered. By the way, he remembered that German and a bit of French his whole life.

He served under General Patton, was awarded the Bronze Star, and the Purple Heart. When Joe was wounded in the war, Gerry wrote to him friendly, caring letters, no hint of romance, but kind words. When Gerry was at Lynchburg College, she was writing regularly to three or four guys at once. At this point, her mom gently reminded her that one day soon the war would be over and all of these guys would be returning. So Gerry got busy writing “dear John” letters. But the kindness with which he wrote Joe was different.

Gerry got Joe to ask her to a banquet at their church, when he returned from the war. Joe says, it was as though they were honed in on each other, two people together in a crowd, a significant memory. So they dated, and Joe took her on some exciting dates, such as the one in which he picked her up in a Model A, took her to the farm, where she sat on the fence, while Joe dug a well while she watched him. Then he took her home; with this kind of dating panache, it’s fortunate that Joe ever got married. (It was much better than the date on which the Model A caught on fire.) They were married in 1946, at Franklin Baptist church in Lynchburg.

Joe was working other jobs after they got married, when he was accepted into the Pittsburgh Art Institute. So in 1949 when Mr. Carr called the art institute for a recommendation, the administration put forth Joe’s name, and he was hired into a two-man ad firm with a part-time secretary. When Joe finally retired from Long, Haymes, and Carr, the agency had over 100 employees.

In work, Joe was known as a congruent man. He did not do anything false. At times he would come back to a client who had accepted Joe’s bid, and ask, “Can you stay in business at this price?” His word was solid; he was quietly generous. His agency looked like Mad Men without all the drinking and sex, but all that elegance and hard work. These three men worked together for years and stayed friends—a rarity these days.

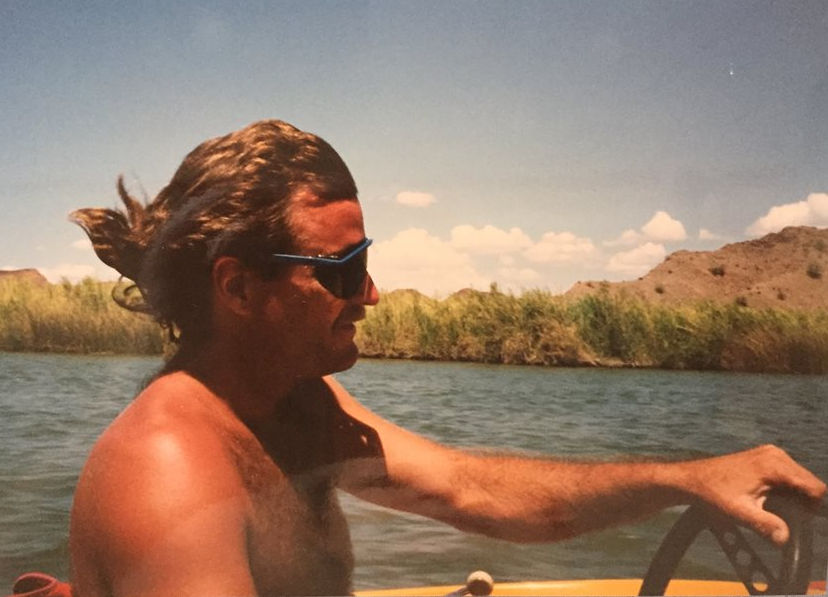

In Joe’s world, you could do anything you wanted to. It was this kind of attention to detail and can-do attitude that enabled Joe to succeed at so much in life. Joe believed in a three-step process: read and study books about the subject; practice it; then do it. This applied to his love of sports cars, of making furniture, of painting, of sailing, and of golf, just to name his major interests. As Yoda said, “Do or do not. There is no try.” Joe believed that.

Joe read widely his whole life. His curiosity seemed boundless. “I always want to know more,” he said, “so I am always reading.” He believed in anticipation, challenge, then accomplishment.

He taught all children to play golf, something they all still love. He taught his children to love the difficult game by taking them out on Sunday afternoons in the spring to Tanglewood par 3. He played with his friends here, the Gangsome he called them. It was a sad defining moment when his health finally failed and cleaned out his golf locker at the country club.

He also taught all his children to drive, and he was a great driver. He raced, you all know, MG-A and TR3. In his first race he came in third, then he never came in that low again, always 1st or 2nd from then out. “You have the coolest dad,” one friend of Peggy’s told her. “He looks like Sean Connery in those sports cars.” He was proud that he’d never been in an auto accident only gotten three traffic tickets his entire life, and each of those were questionable, he contended. He was a precise driver. And when Doug totaled his father’s `67 Camaro, Joe was angry, but didn’t swear or cuss him out. In fact, none of his children remember him using bad language at all.

Speaking of precision, Joe swam very well, elegantly in fact. His swimming was graceful, not in an OCD way, but no wasted movement, never a ripple. He would glide, and flow. It’s an apt metaphor for his whole life, actually.

In 1961, he took Doug and Ross to NYC. I think it was supposed to be a family trip, but Gerry got sick, so it was just he and his sons, then 6 and 10. He took them to the Statue of Liberty, Coney Island; they rode the subway everywhere, and went to two Broadway shows, Camelot and My Fair Lady. He got up early one morning to go and get tickets for the three of them to see a live TV game show. While he was waiting in line, they pulled him out to be a contestant, so he had to call back to the hotel and make arrangements for his boys.

Joe also loved to sail, which he taught himself to do. Peggy remembers that one of her spring breaks he chartered a 27-foot boat to sail for the week. The first day they went out there was a small craft weather advisory warning, but Peggy was never worried. Joe would know what to do, because he knew what he was doing and he was prepared. Coming in that day, the wind was blowing, and theirs was pretty much the only boat out. They came off the dock and passing by a restaurant a woman said to them, “I so envy you.” He published a story about his adventures in a sailing magazine. It was the only story he ever submitted for publication, so he enjoyed a 100% acceptance rate.

Naturally he could paint well. His children were used to having original art in their rooms and around the house. Joe would ask them what they wanted—a war scene for Doug, horses for Peggy—then he’d paint it. And they loved to watch him paint too. He didn’t think his art was brilliant—Gerry rescued a number of his painting from the trash heap, some of which still exist. And he helped one young man, Johnny, to hear his own call to become an artist. Johnny looked at Joe’s life, and realized his own love for art could lead him to a career he loved too.

He made furniture, another thing he taught himself to do. He read and studied, made mock ups of dovetail joints and Queen Anne legs (the chairs not those of the Queen). He would put together his creations first without glue first, and he could these so well that they would get stay together. Doug remembers him watching new Yankee Workshop, a PBS show about woodworking. When the show host finish whatever he was working on, he commented, “There, not bad.” To which Joe replied, “Looks sloppy to me.”

Joe had a dark side. He smoked until he was 45, quitting when Peggy was in Junior High; quitting showed such strength of character. He loved Moose Track Ice Cream and Bean & Bacon soup from Mayberry, Godiva chocolates. But his worse vice of all was his love of puns. This loyal flaw of his infected the whole family, and meals would see the puns fly. Birthday cards were especially groan-worthy.

It was his deep love of words, of course that lead him to love puns. He adored correct grammar, and taught his children to love it too. He could find the right words to fix; he was perspicacious, having insight into the true nature of things. Before computers, he had to write in whatever font he was choosing for an ad, so he knew dozens. His ads were lot like his life: a well-chosen image and a few brilliant words. He said a billboard on the highway had to keep people’s attention 2-3 seconds, so you had to get your point across cleanly and clearly. He edited a few books for his friends, and he wrote an occasional column for the Winston-Salem paper too.

Joe left lots of different legacies, some tangible, some less so. He loved all of you, I’m sure you know that. He was a robust man, full of the love of God and people, and the sweet life he’d be given. No one ever heard him complain. He was a reflective man, endlessly fascinated by people. The Apostle Paul said in Eph 2.10, “We are God’s workmanship,” and the Greek word used there is poiema, which means “work of art, or poem,” or better “masterpiece.” Joe Haymes was one of God’s works of art, which he freely shared with others. He brought together a curious and quick mind, compassionate heart, dedicated service, deep appreciation for life, a gentle spirit and deep faith. The guiding principle of his life was to love God and love other people. One of his sons said to me, “All that I am is what he gave to me.” I know of no better witness to a life well lived than that.