William Carson Parnell

A Life Restored

Memoir by Michael Usey

October 23, 2001

The last lines in Shakespeare’s play King Lear are spoken by Edgar, son of Gloucester. He and the Earl of Kent are surrounded by tragedy when Edgar ends the play with these lines:

The weight of this sad time we must obey,

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest hath borne most; we that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long.[1]

These lines are especially true after thousands died in the rumble of the World Trade Center and Pentagon, in the midst of anthrax, and now a ground war in Afghanistan. Sad enough times in our country, now made worse to all of us here by the premature death of Bill Parnell, a man who loved life, his wife, and his friends, his dogs, and in fact loved Shakespeare. The weight of this sad time we must obey, Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

How do you sum up 53 years in fifteen minutes? You can’t of course, reverberations of Bill’s life will echo though those who knew him best, and your stories about him will continue today and after. You can share them with his best friend, Betsy. He met Betsy at a bar named Papillion, French for “butterfly.” Betsy was 23, Bill 32, when she came up to him and made small talk for 10 minutes. “Can I call you?” he asked. Sure, she said, I live with my parents so you can call me there, giving him her name and address but not the number. He did call, the next night, and then they played phone tag, until he missed her call back. The next day he sent her a dozen carnations to her school and with a note that said, “Sorry I missed your call.”

At dinner on their first date, Bill said to Betsy, “I’ve been married twice and I have two children. Do you want me to take you back home now?” Betsy said no, and this was her first encounter with one of Bill’s key traits: his honesty. Later than same night Bill took her to visit his closest friend Art, which is another of his key characteristics: Bill knew how to keep friends. He had several life long friends; most of us don’t, but Bill had them and knew how to be a friend. He has friends from high school like Art who remembers their first job together at Big Bear grocery store, where Bill got in trouble for eating banana pudding in the cooler on the clock. After meeting Betsy, Bill told Art, “I met a school teacher and she wears dresses all the time!”

Betsy has been a part of a Bible study here that has been studying the Song of Song, the erotic Hebrew love poetry in the Bible. Bill said to her, “Now you’re not going to get all religious on me, are you?” and he kidded her, “They take up a collection each time, right?” The love poem of the Song ends with these words, which Dorisanne just read:

Set me as a seal over your heart, like a seal on your arm

For love is as strong as death, passion as fierce as the grave.

It burns like a blazing fire, like the flame of God.

Many waters cannot quench love, rivers cannot wash it away.

If one were to give all the wealth of his house for love,

It would be utterly scorned. (Song 8.6-7)

“Love is as strong a death, passion as fierce as the grave.” These words were perhaps spoke at funerals 4000 years ago, and are as true now. Having talked with Betsy in depth, it’s clear to me it is true here.

Betsy’s parents weren’t immediately sold on Bill—he had been married before—but they quickly came around. As his friend said, “This time Bill got it right,” meaning Betsy. Later her parents would comment that the best thing they had ever done was move away from Greensboro to Oriental, since when Bill and Betsy came to visit, they’d have to spend the night. It was then they got to know their son-in-law when and come to love him deeply.

They came to know, as many of you here did, that Bill was a caring person. He didn’t shower people with words, or tell them that he loved them. But his actions showed it clearly. When Betsy was getting ready for a trip, he always made sure her car was clean and gassed, tires armor-all’d, oil changed. Once in line at J&S cafeteria, Bill struck up a conversation with an older man who was also an ex-Marine like Bill. Chatting with him to the end of line, Bill paid for the man and his wife as well, a small unpretentious action to honor an older Marine. The couple was touched. When the neighbor down the street wanted him to help her ailing grass—Bill was proud of his lawn and fortified his grass with ironite and 10-10-10—so he did help her, refusing her offers of repayment.

And Bill’s sense of humor was subtle and consistent. He loved to buy toys, mainly for his dogs. He bought and played a kazoo and a train whistle for them. He had juggling pins and taught Michael to juggle; he had a unicycle and he and Betsy would go up to First Lutheran’s parking lot to see if he could right the thing. He loved to laugh, so much so that he would start laughing at a joke he was telling. Michael remembers when he was 10 Bill bought a digital scale, he called Michael to see how much his father weighed. Then he told Michael to wait, which Michael did. A few minutes later, Bill weighted himself again, this time his weight was less. “How’d that happen?” Michael asked Bill. Bill said, “Went to the bathroom.” Marilyn, Art’s wife, said to Betsy, with a twinkle in her eye, “I thought you were going to help him, but my gosh, he’s turned you into him.”

He was a dog-focused individual. If he saw a loose dog in the neighborhood, he’d ask Betsy, “Whose dog is that?” and try and get the dog to come to him, which wasn’t hard. He carried dog treats in his pocket to distribute to his and other dogs. And he worried about his dogs when they were away. How can you not love a person who loves dogs so much and so well? In the Jewish story of Tobit, a dog accompanies Tobit and the archangel on the dangerous journey, and it that dog who symbolizes God’s continued presence to the travelers amidst all the dangers of the road. Maybe it is the same with Bill’s life. Bill’s remains are interned with those of two of his most beloved dogs, Max and Mini. Max lived until he was 12—a long time for a boxer, and the sign of a well-cared for companion. Mini died on Good Friday, so perhaps the three are even now running and romping at play in the fields of the Lord.

Bill worked hard. Having grown up in a single parent home in which there was not much to go around, most everything Bill had was due to his hard work. He wasn’t overly materially focused, but he took care of what he had, and appreciated it. He loved to fix things. Years ago, when he was still fixing copiers as his job he found a copier discarded in the trash. He took it home, had it apart in his bedroom for three months, before he fixed and sold it. Bill had political savvy too: he worked his way up to management in IKON, and was well regarded by his coworkers—something anyone can be proud of.

He brought that political savvy to his activities in the neighborhood association. He didn’t want all of the activities to be solely children oriented, and, when developers came to level the woods in back of their homes, Bill organized the neighborhood to oppose them. In that action, he was articulate in his opposition and successful in their argument. The developers changed their plans.

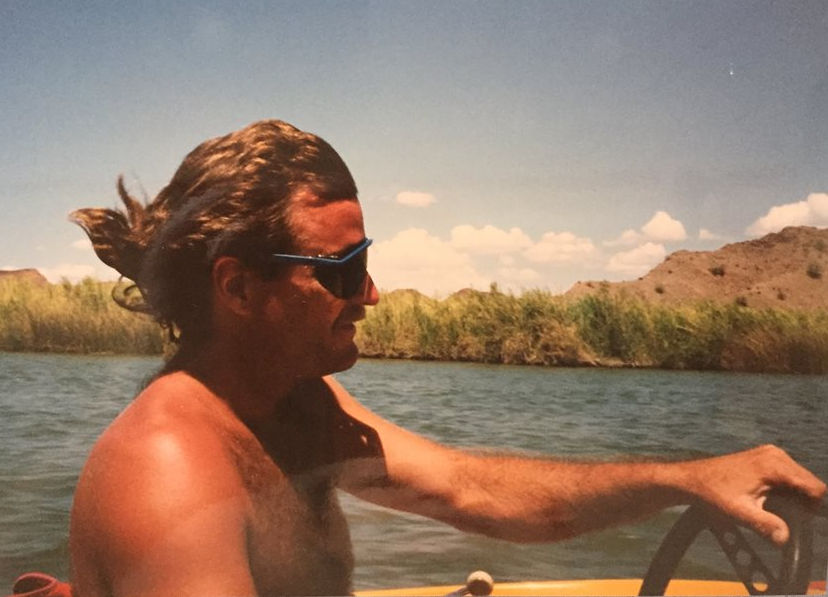

He was intensely interested in life. He bought books about Shakespeare and Spanish, and he loved words and wordplay. He deeply loved music and was at one time a drummer. For a while he had a 120 gallon saltwater aquarium, complete with wave action and lights that simulated dawn and dusk. Later on, he would own a Harley, an 1984 low rider, with a seat and sissy bar on the back so that Betsy could go with him. Wherever he went, he wanted his wife with them. He loved her company, and they loved being together. Bill was not one of those men who are someone else when their wives are not around. He wasn’t coarse, but instead was always a gentleman, a person of integrity—as Marilyn described him, “someone you looked forward to being with.” On a hot rod trip to Myrtle Beach, when some of the other men voted to leave the wives behind, Bill said simply, “No, Betsy’s going.” His last hobby was a 1937 Ford Slantback, similar to the kind ZZ Top drives. The garage was his domain, and caring for his cars and cleaning them his hobby.

What each person really desires, of course, is to count—to count for something and to count to someone. To come to the end of a day—or the end of a life—with the satisfaction of having stood for what is good, with the joy of having been loved and having loved in return, with the memory of having shown mercy, and with the peace of having walked with God: these are the true treasures of life. Bill’s life wasn’t all sweetness and light: his father abandoned the family early on; Bill wrestled with diabetes, a truly terrible disease, and he and one of his sons were estranged from each other at some point in adulthood. Nor was Bill a Christian—he didn’t care for organized religion. (He should have seen a congregation like this one, which is anything but organized.) Like many other people, he kept whatever faith he had to himself. He told Betsy he believed in God and prayed, but this was a deeply private part of himself. Whether or not he believed in God, God believes in him. Bill wanted his life to count—to count for something and to someone—like to all those here, who have a gathered to honor a man who loved his friends, his dogs and whatever other canines he came across. Bill loved words, hot rods, clean cars, exotic fish, his work, his neighborhood and especially his beloved wife and best friend, Betsy. Love is as strong as death, passion as fierce as the grave—especially Bill’s for Betsy, and Betsy’s for Bill, and God for both of them. The weight of this sad time we must obey, Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

[1] King Lear, V, iii, 324-327.