Jack Edwards

Memoir by Michael Usey

January 21, 2001

The priest Zachariah is one of my favorite characters in the Bible. After all, I named one of my sons after him. He is old when we first meet him in Luke’s story of Jesus, and he is without children. When an angel appears to him and tells him that he and his wife Elizabeth will have a son in their old age, old Zachariah doesn’t believe a word of it. The angel strikes him mute and deaf, probably to give Zack some time to think about it. He does, and when his son is born, he names him John, the last and greatest of the prophets, and the one who will announce God’s messiah.

When he can finally talk again, Zachariah begins a remarkable blessing. He blesses God, his son, his life, and all the remarkable things God is doing. Most notably, he blesses that God for opposing the rich and powerful, and remembering the despised and lowly. Zachariah ends his wonderful psalm with these words, found in Luke’s gospel:

By the tender mercy of our God,

The dawn from on high will break upon us,

To give light to those who sit in darkness, and in the shadow of death,

To guide our feet into the way of peace. [Luke 1.78-79]

There is a lot in the passage that reminds me of my friend, Jack Edwards. Like Zack, Jack lived a long time, he was faithful to the worship of God, and he was sometimes skeptical. He knew how to bless God and his rich life. And both Zack and Jack loved their wives and loved justice.

If you knew Jack, then chances are you know that he was bright and curious. He was extremely well-read. On his shelves were classics that many claimed to have read, but had not. Jack read them all, and many others. He not only subscribed to Time magazine his whole life; he also actually read it through. He passed this deep love for reading on to his children, Judy and Derwood. In fact, he taught Judy to read on his lap by reading with her the comics in the paper and Time. He took them both to the library many, many times. He took classes in psychology. He loved historical novels and biographies and autobiographies. Jack didn’t have the formal education that he wished he had, but he was self-educated, and better read that many folks with advanced degrees.

Jack was very bright. He smoked a pack of Lucky Strikes a day, until, in 1965 he read in Time magazine the Surgeon General’s report that smoking caused lung cancer. He quit immediately—no slacking off, no trying ten times—and didn’t smoke again. This is an absolutely amazing part of Jack, especially as I think about my father, a long time heavy smoker, and note how difficult that habit is to break. He also was interested in the stock market, and taught himself all about it. He did well in it too, apparently. He bought some stock that, after years of splitting and merging, ended up as Viacom.

And, if you knew Jack, then you know that this deep curiosity of Jack’s extended to people around him. One of the most defining characteristics of this charming and stubborn man was his real interest in the people he met, and his genuine concern for their well-being. I listened to Jack while he was waiting for a room in the emergency room of Wesley Long as he told me all about the nurses who were attending him. “This one’s from Michigan, just like your wife.” I never visited him in the hospital when he didn’t know all about the health care providers with him, be they doctors, nurses, or custodians. He asked them questions about their lives, just as he had done with thousands of others. They might have wanted to talk about him and how he was feeling, but he wanted to know about them. Sure, some of it was he was uncomfortable with the focus on him, but most of it I believe was Jack’s genuine interested in people. If you went to visit Jack, you had to be careful that he didn’t get you to do all the talking. Of course, he didn’t just listen, he loved to discuss and to argue. Jack loved a good debate, and to throw discussions into a more intense plane by playing the devil’s advocate. One time a cemetery plot salesmen had come by, and Jack had gotten him all flustered, since Jack didn’t believe in planning for death when there was so much living to do. When the salesman left, Jack calmly walked in the kitchen, and without a word, jumped in the air and clicked his heels. A lovely image of him living out what had just argued: celebrating the now. He was deeply curious about other people and their ideas, and self-effacing, a rare and refreshing quality in today’s narcissistic culture.

If you knew Jack Edwards, then you might know that his growing up years were difficult. He was the youngest child, and his father died in an elevator accident at work when Jack was two. His stepfather was a mean man, and most of his childhood Jack was silent about, except that it was rough. Jack was a simple man, yet quite complicated, and there is much about his life only he knew. Judy overheard him say once (when Jack thought she was asleep in the back of the car on the way to the beach) that one time when he was young, the family only had chicken feed to eat. Interestingly, he grew up on the very property that he lived on until his death.

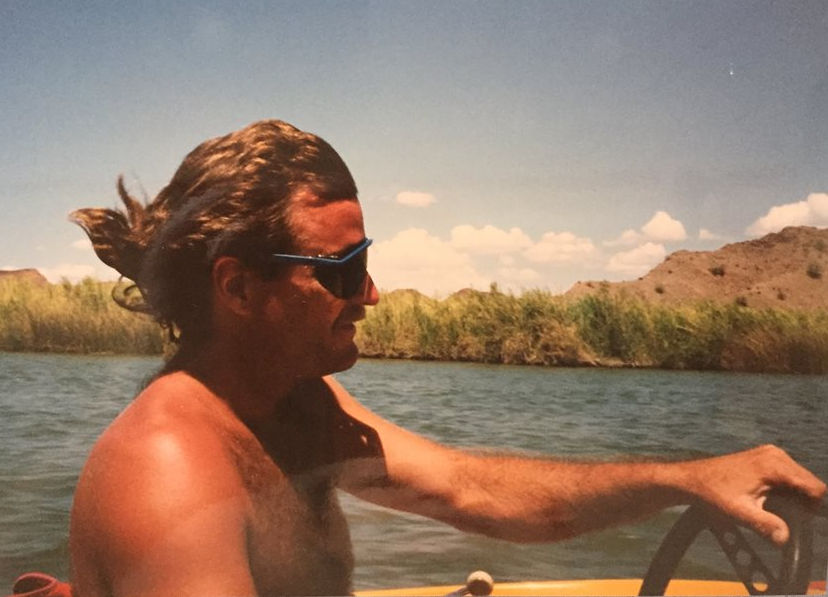

He was something of a hooligan as a kid, wrestling with the other kids on the block (and back then it was a very big block). He raced and wrestled Tike Marley, a big kid with long hair, and Tike used to swing him around by his long hair. Jack had hair back then, curly hair in fact. Most of his early childhood pictures were destroyed when lightening struck his and Bernice’s house in 1956, and burned it to the ground. But his children found some of them and you can see them here today. Jack and his friends used to like getting the police to chase them, and they’d bait them in and around the winding, confusing roads of Hamilton Lakes. One of them could sound like a woman yelling for help–”Help! I’m being kidnapped”–then they’d run like all get out.

If you knew Jack, then you probably knew he was happiest outdoors. He was a Boy Scout leader here at College Park, Assistant Scout Master in fact. He loved camping and hiking at places like Hanging Rock and Moore’s Knob. He absolutely loved to grow things. Jack grew azaleas, and at one time he had over ten thousand in a greenhouse he and Derwood built. He developed his own variety of camellias, and all of those huge pine trees in the back of the Edward’s house, he and his son planted—over 100 of them. When he was younger, he played golf every Sunday after church, and he was quite good—his brother was the N.C. amateur tournament golf champion, and Jack had skill at that frustrating game too. He and Bernice would sit for hours, watching the squirrels and the birds.

If you knew Jack Edwards, then you know he loved his family. He adored his children and especially his grandchildren. He taught Derwood to make kites from wax paper and broom straw that were so light and strong they would fly for hours. They’d fly them out behind the cemetery there, and when it finally got dark, they’d stake them up and often find them flying still the next morning. He taught Judy to walk at the Methodist church across the street, the same place he taught Derwood to ride a bicycle. It was also the same place he tried to teach Judy to drive. Their car was a stick shift—not easy to learn—Judy stalled it often. Finally when she stalled it in the middle of Muir’s chapel road, Jack simply got out of the car, told her to get home as best she could, and then he walked home. By the time Derwood came along, he learned his limits: he hired someone to teach his son to drive. Judy’s sons spent 5-6 weeks with him and Bernice during the summer. Jack threw baseballs to them for hours, so much so that they became excellent fielders.

If you knew Jack, even for just a little while, then you realize that he appreciated a joke—his or someone else’s. He always wrote his name “Jack Edwards” on his seat cushion at work so that it wouldn’t be swiped. But some wag at work was always adding an “S” as his middle initial, so that his cushion then read, “Jack S. Edwards.” He got a kick out of this. He and Maston Stone had a running joke for about 40 years. Jack would say to Maston, “Hey Maston, do you have any money I could borrow?” Maston would say, “Well, I have 35 cents.” “Do you have it with you?” Jack would ask earnestly. “Well, no, I have it at home.” “When can you bring it?” Jack would say, and on and on. Many, many years later, he’d still say to Maston, “Did you bring that 35 cents yet?” He was always joking and carrying on with his friends Joe White, Maston, Dan Cottrell, Reid Touchstone, and many others.

If you knew Jack well, then you might have discovered that Jack was a Baptist radical, truly an old school Christian liberal. His whole working career he worked for Mo-Jud supervising 300 women. Although he was middle management, his sympathy was definitely for the well-being of the workers. He saw how management did not always act in the best interest of its employees. Then and now, it’s rare to find a manager who has the integrity to be pro-worker. One time working over one of the machines with hundreds of needles on a metal plate above his head, he leaned in too far. The needles stuck him in the forehead, making several neat rows of bloody pinholes. He hated the McCarthy-ism of the 50s, and he used to buy copies of The Daily Worker, not only to read but to support the cause. It is fashion now, 50 years later to decry the Communist witch hunts, but too few had the courage to do so then. Jack had this courage.

He worked hard, 7 to 4 in the noise, dust, and lint of the plant, with only 2 weeks off a years, weeks that he spent at the beach with his family. When his daughter Judy was old enough, he had her work at the mill with him for 2 weeks, as an incentive to her to stay in school and to keep studying hard. When he came home at night, the phone would begin to ring with women telling him why they wouldn’t be at work the next day—which is the reason he grew quickly to hate the telephone.

I discovered Jack’s radical nature after I had been here at College Park for only a few months. He had told me when I first came that he could no longer hear my sermons (from the years at the mill, no doubt), but that, if I would send them to him, he would read them. I did, and after I was here about 6 months, I send him a copy of an edgy sermon I had preached on abortion, a sermon that was a response to an imbroglio here at the church. Jack found me the next week in my study, and said, “Preacher, I read your sermon on abortion, and I agree with every word of it, and if when you know me better, you’ll realize I don’t say so that lightly.” It was a true word of grace to a young minister, and I’ll always love Jack for saying it. As a matter of fact, he often gave me positive feedback that proved he read my sermons seriously. This constant positive feedback to this odd young minister was a light for me during many a gray week when I wondered whether my words meant anything to anyone. He ministered to me, as he did to many others.

If you knew Jack, then you knew he loved his wife Bernice. They were married 60 years, and they dated 5 years before that. Yet he often said to her, “I so wish I’d met you earlier in my life.” The night before he died he said to her, “Bernice, have I told you enough that I love you?” No one disputes that he did.

If you knew Jack Edwards, then you knew that he loved God, people, and his church. He believed that everyone had a chance to find their faith. He trained his children in the faith, and to know right from wrong. He was a good man, who was deeply compassionate about those around him. If we know how much we love God by how lovingly we act towards people, then we know clearly of Jack’s great love for God demonstrated in his active love for people. Like Zachariah said many, many years ago, times of pain can result in God’s peace. “By the tender mercy of our God,” we have been blessed to know Jack Edwards. “The dawn from on high broke upon us,” in his rich life, and through his life we experienced God’s presence and love. In remembering his life we “give light to those who sit in darkness, and in the shadow of death,” which—right now– is all of us this afternoon mourning the loss of this great man. But, by his example and through his memory, God will continue “to guide our feet into the way of peace.” [Luke 1.78-79] Amen.